In February of 2015 Will sat on a hotel balcony in Puerto Escondido, Mexico and wrote a blog post. It was intended to kind of give ourselves a kick in the ass; we were teetering on the cusp of applying for residency in Mexico or doing something dramatically different.

Of course, we went for dramatic. Or at least I think we did. I do have a fondness for flair.

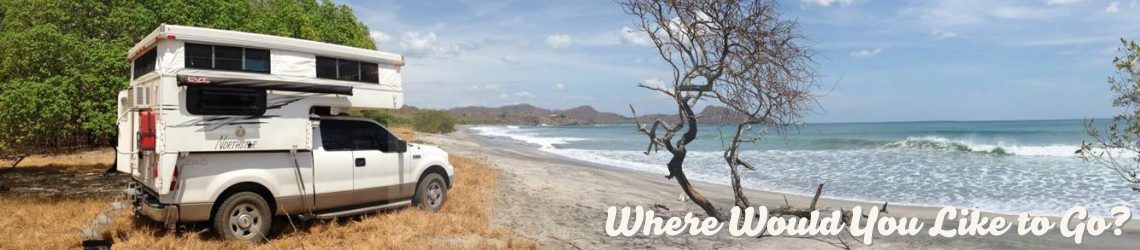

And you all know what happened next. We bought Moby, we bought way too much shit we thought we’d need and didn’t, and hit the road; starry eyed and brimming with confidence, the kind of combination that always means you’re just around the corner from a massive disappointment.

We’ve had several of those disappointments in the nearly two years since we left the United States and set our sights on Ushuaia, Argentina. We were robbed of nearly everything of value in Barranquilla, Colombia; the ubiquitous mañana kept us delayed in uninspiring places for weeks at a time; places we loved bore no resemblance to the way they had fit into our current story; we had to sacrifice a good deal of sightseeing as we were always chasing wifi in order to work.

Disappointment is inevitable when you travel, no matter how you do it. You need a damn selfie stick to get a shitty photo of the Mona Lisa because of the crowds. Your flight is delayed so you miss your connection and the airline graciously gives you a coupon for McDonald’s. A sudden storm means you’re trudging around Chichen Itza with no umbrella and wet shoes. If a trip goes off without at least one hiccup then you’ve got some wizardry on your side.

But it’s every traveler’s nightmare that a trip will be canceled or cut short due to circumstances beyond their control. Circumstances that were never, ever expected.

We have met so many different people from so many different places on this journey. Older couples who have a pension and a retirement to piss away however they please. Young people who have saved money and have a small window of time before they have to go back to work. Families who have decided that driving their kids around South America is better than any school. Seriously, you’d be surprised at the many different kinds of people who undertake this trip.

We have a lot of people tell us things like, “I really wish I could do what you do but we have kids.” I think of all the campgrounds we’ve visited that are teeming with kids, finding bath toys in communal showers, and watching superhero moms simultaneously keep one kid from drowning while effortlessly preparing scrambled eggs for five on a propane stove with another wailing kid attached to her leg.

It’s not your kids you need to worry about if you want to take a trip like this; they’ll be fine. In fact, they’ll be more than fine. They’ll be amazing little shits who will grow up to speak four languages and be the problem solvers of the world.

It’s your aging parents that you need to worry about.

My mom’s health has been declining for some time but it’s been gradual and I’ve never really had cause to worry. My daughter was living with her to help her out and everything was fine. I called her about once a week to chat and she always kept up with us on Facebook. I think she took a lot of joy in following along on our journey.

About two months ago I got a message from my daughter. She had recently taken the move to working full time and was out of the house for the majority of the day. She was worried that my mom needed more attention than she could give. She’s also a young woman with a life of her own. Her residence there was never supposed to be permanent; we just never discussed the time when she’d need or want to move out on her own.

Until now.

What do you do when you’re somewhere in the middle of a trip of indeterminable length with your partner and one of you has to stop? How do you let go of the goal you plotted out together? This isn’t like a few months backpacking around Asia; one of you can leave and say, “I’ll see you in a month or so!” We have at least a year or more before we can feel comfortable saying that we’re done.

But the truth is that we are not done. I am done.

I leave for the states in 12 days. Will does not. A mutual decision was made; Will is going to finish the trip on his own. Our relationship is as good as it ever was, probably better, and I don’t anticipate that changing.

But I have to go.

I am sad. I am sad that I’ll miss Buenos Aires, one of the cities I was most looking forward to. I’m sad that I won’t go to Easter Island, something we had very seriously considered as part of this journey. I’m sad that I won’t revel in wine country or try my hand at polo in Argentina. I’m sad that I won’t be able to say, “I did it. I drove a damn truck to the southernmost tip of the Americas.”

But most of all I’m sad to be leaving my best friend behind.

The cynic in me tends to turn my nose up at silver linings but I do think there is one here. I’m excited to spend time with my mom. We have not lived close enough to each other for regular visits in years. I like her; she’s a really cool person who is fun to be around. While I don’t really love being in the states it’s been a long time since I’ve spent more than a few weeks there and it could be a lot worse than northern Utah.

But most of all I guess I feel a sense of privilege. We’re all going to get old one day; you, me, and everyone we know. If all of us had a person who said, “I’ll help” when the need arises can you imagine how great would feel? I can help my mom stay in her home. I can help my mom in her garden this summer. I can drive my mom up to Bear Lake for raspberry milkshakes. I can simply be there so she’s not alone.

That’s a privilege.

I’ve learned so much on this trip that I somehow wonder how I survived before. Pieces of my DNA have been fundamentally altered; that’s a given when you throw yourself into a sink or swim situation the size of two continents. I’ve become more brave, I’ve become more compassionate, I’ve become more humble, I’ve become more intelligent, I’ve become more of the type of person I’ve always wanted to be.

That’s a privilege too.

So that’s it. That’s all. That’s how it ends. I leave Rio for Utah and Will leaves Rio for the next place down the line. Where that might be is up to him now I suppose. And just like the moment we began planning this trip, this part too is indeterminable. What happens next lives somewhere in the great wide open.

But that’s how it always is, isn’t it?

I am not a physician nor do I have scientific training in tropical medicine. Please don’t take this as medical advice.

I’ll never forget the day I collapsed onto the street in Siem Reap, Cambodia, two weeks into a seven week trip through that country and Thailand. I had been sick for a few days but we decided to take the bus to Phnom Penh anyway, even though I was burning up with fever that morning. When I hit the ground I dreamily thought the heat of the pavement felt cool on my skin.

Suffice it to say I never got on that bus. Instead I found myself in a Siem Reap hospital, pumped full of fluids and painkillers, and diagnosed with dengue fever. I was released from the hospital after a day or so but it was still a week before I could travel and three more weeks before I started to feel better, really better.

That was almost 14 years ago. Since that time I’ve been the one who is always covered in repellent. I’m the one that hides behind screens at the merest hint of that maddening, whiny buzz in my ear. I’m the one that checks my body for the tell-tale rash if I feel ill after those bitches have pierced my skin with their virus laden proboscises. I’ve been lucky since that time in Cambodia but my luck ran out a month ago in Asuncion, Paraguay.

Mosquitos have been the scourge of the earth and a bane to humankind for millennia. In his book “Slave Trade” author and Georgetown professor John McNeill states that, until the mid-twentieth century, more battle troops were killed by mosquito borne diseases than were killed in actual combat. Malaria was the disease du jour at that time and troops who had not been exposed to the disease promptly got sick and died.

Mosquitos and malaria were also part of the reason why European colonists were unable to penetrate the interior of Africa until the early 1800’s. Quinine, a product of the Cinchona tree native to South America, was brought back to Europe by the conquistadors but it wasn’t until later that British colonists in India discovered that it aided in one’s recover from malaria. The bitter drink was made more palatable by adding sugar and water. Of course, the British took that one tasty step further and added gin to the mixture. What better way to feel like you’re conquering a deadly disease than to do so by knocking back a few G & T’s?

While Africa’s dark interior remained off limits the coastal regions were fair game and in the 15th century when the slave trade began Africa’s mosquitos were stowaways in large numbers. When this same trade expanded to the Caribbean and North America a new breeding ground was formed and those previously unheard of diseases flourished. Mosquitos are opportunists; give them some stagnant water and stable temperatures and they’re almost unstoppable.

Malaria was simply the start. As science progressed more mosquito borne diseases were identified and the numbers are staggering. There’s West Nile virus, equine encephalitis (yes, humans can get it from infected horses), dengue fever, Japanese B encephalitis, yellow fever, malaria, chikungunya, Saint Louis encephalitis, and zika. These are just a few of the mosquito borne diseases that humans contract but they’re the ones most world health organizations pay attention to.

So if you’re traveling to the tropics where these diseases flourish you might think about heading over to the clinic and getting a vaccination, right? Wrong. Currently, the only reliable vaccines available are for yellow fever and Japanese B encephalitis. A vaccine for dengue is available in limited supply in countries hardest hit by outbreaks but it’s not entirely effective. And if you’re in the market for a yellow fever shot you might be out of luck. A current outbreak of the disease in Brazil has effectively depleted the world’s supply of the vaccine. There is no vaccine for malaria but prophylactic medications like doxycycline can reduce your chances of contracting the virus.

As a traveler to mosquito heaven I am keenly aware of the dangers. I was vaccinated for yellow fever in 2011 prior to our trip to the Peruvian Amazon. As a previous dengue victim the vaccine for the virus was recommended to me (priority is given to the elderly, those with compromised immune systems, and people who have had the virus before) but it’s a three shot series over the course of 18 months and weighs in at a hefty 450 USD.

So, back to Asuncion, Paraguay. We had taken a break from camper life and were ensconced in a lovely little apartment. I woke up one morning feeling off and within a few hours I had a massive headache, a fever, and joint pain. I spent that day in bed gulping water and Tylenol and hoping it was just a flu. By the next day I knew I had to see a doctor. I hurled myself into a cab and headed to the nearest hospital. The moment I mentioned dengue to the reception staff I was hustled straight to an exam room. The doctor asked me about my symptoms and promptly sent me to the lab for bloodwork.

As I stated earlier I am no medical professional. However, while I waited for my blood to be scrutinized I did turn to Doctor Google. What they were looking for in my blood was the actual presence of the virus and a check of my platelet and white blood cell count. However, the test for the viral presence is a crapshoot; if the patient has the test too early after symptom onset it’s inconclusive. Antibody tests can also be inconclusive. The test can indicate an active infection or simply indicate that the patient has had the virus at some time in the past. My results were inconclusive for the virus itself, antibody presence was not tested, and my platelet and white counts were low.

That doctor’s diagnosis? Dengue fever. I was sent home with the standard treatment: fluids, rest, and Tylenol.

However, my symptoms never really progressed to the horror I experienced in Cambodia. After a few days I felt better and the fatigue dissipated within a week or so. When I followed up with a different doctor he surmised that I probably had Zika given the relatively mild symptoms. Perhaps I’ll never know what really happened.

But what I do know is this. If you're traveling in the tropics get your shots. Many countries in the world ask for proof of yellow fever vaccination and have the right to refuse entry to those without that proof. And for those who ask questions like, "Do I need a yellow fever card to get into X country" I simply reply to their question with a question.

Do you want yellow fever?

Because mosquitoes don't care about you. They only care about world domination.

I’m really enjoying my new style of writing. I find myself paying more attention to the things I see and the things I feel. It’s almost as if I’m experiencing this journey in a new light, as cliche as that might sound. So, here are a few of the things I thought about this week, a few photos, and an incredible video that I hope you’ll watch.

Thanks again for following along as I test out this new style AND stay tuned for a full post about how Will and I grossly misinterpreted a church in a salt mine.

We were leaving the Honduran border series of queues and offices, documents in hand that officially cleared us of any further obligation to the country when it hit me hard.

There was a dog, so thin that the bones of her pelvis were so prominent that they completely obscured her genital area. It was hot, even at 10 am, and she was lapping listlessly at a filthy puddle of something that probably contained very little actual water.

I doubt her little doggie life lasted the rest of that day.

It isn’t like I haven’t seen street dogs hours or days from death before. It’s simply a part of life in much of the world. However, after our time in Guatemala and Honduras it was that little dog that broke me, because we all know that when it comes to the impoverished the privileged of the world often tend to focus more on animals than they do people.

I’ve seen the do-gooders. I know some of the do-gooders. And while some do good things to help people it seems that more of them do things to help animals. Shelters, spay and neuter clinics, airline escorts for Mexican and Central American dogs and cats to go to their cushy new homes in the United States or Canada.

All while people are left to lap from the same dirty puddle.

People from all over the world visit Mexico and Central America all the time. They zip line in Costa Rica, frolic on the white sand beaches of Mexico, and dive in the crystal Caribbean waters of Honduras. But more often than not these trips are carefully constructed, staged by tour operators, and guarded by high resort walls. There’s nothing wrong with this; I truly believe everyone should travel and how they do it is their choice.

But what about the things that live outside those tours and walls? What about the people?

I’ve written about this before. Unless you’re a backpacker or overlanding like we are you rarely come into contact with the people who call your dream vacation destination home. Unless they’re mixing your margarita or scraping the callouses from your feet you don’t see them, you don’t ask about their life, and you don’t do these things because you’re on vacation and you deserve to enjoy yourself.

But also, you don’t want to know.

You don’t want to know that your bartender lives in a one room cinder block house. You don’t want to know that the woman carefully polishing your toenails can’t afford to send her kids to school. You don’t want to know that they too suffer, just like the dogs.

I’m as guilty as anyone of turning a blind eye. The simple fact that we can afford to make this trip put us squarely in the middle of the white privilege circle. But even the dead and dying humans on the sidewalks of New Dehli didn’t prepare me for driving the roads of Central America.

I romanticized this trip way too much right from the start. I envisioned wide open beaches, remote jungle villages, and endless adventure. While much of that has been realized too much more of it has not. This is aside from the realization that this mode of travel is really hard. What’s become so difficult for me is passing through these tiny villages, women toeing the edge of the road trying to sell us sacks of unidentifiable food, the desperation so clear on their face as we approach, then the anger when we don’t slow down.

I’ve taken very few photos over the last two months. My instagram feed is bare. That’s not to say that I haven’t wanted to. The haunted and wary eyes of the children that want me to buy gum are definitely photo worthy. These are the types of photos are meant to make you feel something, like the photo of the ash covered, shell shocked Syrian boy on the chair in the hospital. These photos are supposed to make you care.

But you don’t. Or you do but remind yourself how helpless you are and that you have your own problems or children to care for. These are not invalid excuses; we all have our own shit to deal with but the simple fact that we have the option to look away constitutes that white privileged guilt that, well, we’re all pretty much guilty of.

We don’t have to look if we don’t want to.

But on this trip I’ve had to look. Our windows aren’t blacked out, hell, neither are my eyes. There is simply no way not to see the tin and tarp shacks and the barely dressed toddlers in the dirt surrounded by scrawny chickens and heaps of garbage. It’s there, right in front of everybody.

Everybody who looks, that is.

So if you’ve made it this far you might be asking yourself, “Why the hell is she complaining? Why isn’t she doing something?”

I could ask you that same question but you might want to think carefully about your answers.

Do you tip your bartenders and servers in Mexico? Do you buy your ice cream from the man pushing the street cart or do you pop into whatever resembles the local 7-11? Do you avoid a certain city or country because of perceived violence and moan about how great it was in the old days without thinking of the people who have to live there? Do you slip your extra food to a street dog instead of the child who wants desperately to shine your shoes?

I’m not here to shame anyone. Most of the people I know are good people and some of them go above and beyond to serve communities at home and abroad. I’m also not here to set myself apart. I’ve avoided the old man with his hand held out for money, his head held down in shame. I’ve shouted unkind words in Spanish to street kids whose eyes are hardened as they aggressively tell me to buy tortillas after I’ve declined three times.

I sometimes don’t look out the window anymore as we pass through another rural village slapped together from scrap wood and detritus. I don’t see the dull eyes staring at our shiny American vehicle passing through, but I feel them.

I think I’ll feel them for the rest of my life.

Again, I have no answers. You have no answers. Today’s state of affairs around the world has left so many feeling helpless, even those of us in the guilt circle. But one thing we can say as individuals is that I did not do this.

But someone did. Someone left Honduras poverty stricken, someone left Mexico embroiled in violence, someone committed genocide in Guatemala, and someone reduced Syria to an unimaginable and unforgettable photo.

Let’s not mince words here; money rules our world. Corporations are eager to profit from the desperate and governmental officials turn blind eyes but they can certainly feel the money slipped into their dirty hands. Resources are exploited and people are discarded. It happens everywhere, even in your own backyard.

Yet despite everything I’ve said I see people around the world rising up, using their voices, demanding that something resembling humanity be restored in our world. I’ve met people on this trip who fill extra suitcases with medical supplies and books. I know people who live as expats yet do amazing things in their communities to help the local populations. The human ones.

I know people who realize that all is not lost.

So as sad and as frustrating as this all is I’m looking at you. The do gooders who actually do something good.

As for me, I’m digging deep and trying to uncover the real reason for this trip and my purpose in it. And I think part of that purpose begins with always looking out the window.

No matter how bad it is.

I haven’t written a blog post in quite some time. Why? I’m not really sure. The easiest explanation is that I’m lazy and I could just leave it at that. However, deep down in my slothful and sluggish heart I know that’s not true.

I just haven’t really known what to say.

My head has been swirling with ideas for blog posts, haikus, and unfamiliar feelings of something, well, unfamiliar. I’ve heard about it, some of my best friends talk about it and they say it’s important. I’ve never had these feelings until now and while peculiar they’re also special feelings.

This is starting to sound like a cringeworthy 1970’s “Your Changing Body” video you might have seen in 7th grade.

So what is it? It’s living in the moment.

I’m an obsessive worrier. I overplan. Worst case scenario is my middle name. I lose sleep over things that might happen and never do. I lose sleep over things that have happened that I cannot change. Just like whistling and eating horse meat, this idea of living in the moment is truly something I thought I could never, ever do.

Yet here I am, with these strange peaceful feelings washing over me, albeit gently. I’ve definitely not reached the tsunami level of inner peace yet.

So how has that impacted the way I feel about writing? It’s strange because the whole purpose of this blog is to share our experiences with family, friends, and readers. But since my last blog post, which was before Christmas, I haven’t written a thing.

But I’ve wanted to.

I wanted to tell you how painful it was to leave Mexico early because of the civil unrest that went down just after the new year.

I wanted to tell you about how crossing the border into Guatemala felt like being kicked out of my family’s home.

I wanted to tell you about how shitty our first night in Guatemala was and how incredible the following three weeks at Lake Atitlan were.

I wanted to tell you about Antigua, how much fun we had there, and the incredible things we ate. Randy’s Sausage, I’m looking at you.

I wanted to tell you about how we got stuck driving in Guatemala City and almost died multiple times, either from a car crash or from one of us killing the other.

I wanted to tell you about crossing the border into Honduras on a sunny Saturday afternoon and how nice it felt to check off another country as we make our way ever southward.

But the truth here is that I didn’t elaborate on any of those things because I wanted to keep them just between Will and I and the people we’ve shared these experiences with. I wanted to be quiet, thoughtful, and let it all sink in.

And even though I’ve resisted with all my might I wanted to… live in the moment.

Our little blog doesn’t have the readership that might make me want to step back and keep things private. After all, I’ve written a pretty graphic post about how to have sex in a camper. I don’t really care about privacy. I know that there are probably a lot of people who haven’t even noticed the radio silence over here at The Life Nomadic. But by keeping some things to myself I’ve come to understand this trip a little bit better which has also allowed me to get a little bit better at handling it.

I’m still a lazy slob but I’ve been able to pay better attention to what’s happening around me, whether it’s inside the camper or out. And I’ve begun to sweep the floor and shake out the rugs more than once a week.

That’s a huge accomplishment. Huge. Truly spectacular.

No two adventures are exactly alike and I know that ours is vastly different from the trips other overlanders take. Work tends to dominate some of our choices and limits others. I used to feel like that was a hindrance more than anything else; I felt like we weren’t truly embracing the nature of this kind of trip.

But now I know differently. Like it or not, this is what our trip looks like. The location changes every few days or weeks but the fact of the matter is pretty simple.

We live in a camper.

We work in a camper.

We’re driving that camper south and doing the best we can along the way.

And while we have missed out on some opportunities and will continue to miss others that’s just the nature of this adventure. It’s ours and, like it or not, we’ll continue to do these things as best we can.

As far as me? This newfound ability (albeit a fledgling one) called living in the moment has given me something pretty special and that something is more moments, little treasures like the one I had last night.

A field full of dancing fireflies, their booties lit up like a gaudy Christmas tree in a frantic, horny display of luminescence.

Come on, I may have found some peace but I haven’t lost the middle school snark. I just wouldn’t be me without it.

One of the things I was most concerned about before we started this trip was how personal space and overlanding was going to work. Will and I both have written in the past about how much we enjoy our personal space. If you look at the size of the homes we’ve lived in over the last 6+ years you can easily get a sense of just how far away we like to be from each other.

In Taiwan we had a three bedroom, two bath apartment. That’s quite big for Taiwan although I did see some much bigger.

In Peru we had a three bedroom, two bathroom house with a lanai the size of the interior ground floor.

In Abu Dhabi we had a four bedroom, five bathroom home on three levels.

In San Cristobal we had a six bedroom house with six and a half bathrooms.

Of course, all of this was way too much space for two people but either price or circumstances out of our control put us in these ginormous houses and I got used to it.

Now, things are different. I’ve gotten somewhat used to life in a camper. I’ve mastered the turn and twist so one of us can get from the stove to the fridge. I’ve mastered my descent from the bed to the couch to the door if Will is in the aisle. It’s really not so bad.

However, there are those times when I miss those extra bedrooms and bathrooms. Like when I want to stay up til all hours reading and I don’t want to disturb Will. Or when one of us is sick and constant bathroom runs are just easier in another bedroom. Or when we’ve had chili for dinner.

But as I slowly learn that giving up my personal space hasn’t quite been the temper tantrum catastrophe I imagined, there’s now a new personal space and overlanding issue I’ve got to contend with.

Other overlanders.

From the beginning of this trip we’ve pretty much been the only people at every campground we’ve visited. I’ve lamented about that so frequently that you’d think that as soon as we found a campground with other campers in it I might have cried with joy.

This brings us to our current location, La Habana on Zipolite Beach in Oaxaca. It’s about as idyllic a location as you can get. Cabanas with palapa roofs are perched on stilts overlooking one of the nicest beaches I’ve ever seen, electric outlets are available for campers and you back in toward the cabana, leaving the space underneath as your shady lounge area. There’s a tent camping area further down. There’s a restaurant with cheap and tasty food and the bathrooms are spotless.

So what’s the catch. This place is packed. I mean packed to the point that I’m seriously worried about fire. You know, palapas and fireworks are a recipe for disaster and a lot of our fellow campers are taking advantage of the cheap Mexican fireworks. If a fire did start all we could do is run away on foot. Moby is blocked in from every angle. We’d lose everything.

And then there’s our fellow campers. It seems like most of them have been doing this for a while and their comprehension of personal space and overlanding is very different than mine. The boundaries created at this campground are pretty clear. We pay more for our space with electricity and the little lounge area than the tent campers do. However, the tent campers don’t see much wrong with unplugging truck campers to charge their phones.

Without even really asking.

Who does that?

And there are fairly clear paths to the restaurant, main beach, and bathrooms but not very many people use them. That means that people come strolling through our campsite or, in the case of the kids, streaking through, leaving knocked over beer bottles and general mayhem in their wake.

I don’t travel with young kids but I know a lot of people who have. In my imagination when the family finally parks for the night, especially after a long drive, they’re just like “Run, children! Run until you can’t run anymore then do it again. Mommy and Daddy will be over here drinking wine and questioning again why we took a trip like this with you.”

So here we sit, surrounded by French families and couples on all sides. They’ve all kind of banded together because they’re French, I guess, and we’re just these lone North Americans who don’t speak French and many of them don’t speak Spanish. No one is rude; they’re just kind of cliquey.

It kind of makes me regret that degree in Mandarin I thought would be so useful.

So is it just me, corn fed and raised with the concepts of personal space and boundaries shoved down my throat? Is that why the French parents of the naked baby who is currently wandering through our camp space, dangerously close to bottles and lighters, don’t seem to care or even notice? Look, I’m all for parents traveling the world with their children but amongst the homeschooling and worldschooling activities was the notion of boundaries left out of the curriculum?

Or is personal space and overlanding an idea I should just abandon, like I did with my hairdryer and concept of time?

These are the thoughts I’ll be thinking today as I continue to keep stray babies away from the glass and the ashtrays.

So as I sit here, right behind Moby in my comfy chair gazing out at the Pacific Ocean there is a naked French guy not three feet away from me. In fact, it was just five minutes ago that he approached me to give me a book in English.

I’m sitting. He’s standing. So there I was, eye level with his dick.

Awkward? A little bit, but he’s a pretty good looking French guy and it’s really hard to make eye contact when there’s a friendly cock in your face, but I maintained.

We’re in Zipolite, one of the many, I’m sure, nude beaches in Mexico.

This is not my first naked beach rodeo. When I lived in Hawaii a small beach called Kehena was a haven for nudists. I’ll never forget my first time there, sitting on the sand and talking with my friends when someone tapped my shoulder and asked if he could borrow my lighter. I turned around to a face full of old man junk.

I rarely went to Kehena after that.

I have zero problems with nudists. If you want to literally hang out, go for it. I just don’t know how to act. And after my few visits to Kehena in Hawaii I decided that the people who get naked at nude beaches are generally the people you don’t want to see naked.

I think that’s far from the case at this nude beach in Mexico. We’re staying at a campground/hostel type place very popular with backpackers. Most backpackers, in my opinion, tend to be young and pretty fit. They also seem to have very relaxed attitudes about pretty much everything, so here they’re naked. And frankly, it’s not so bad to see young and beautiful people in the buff, wandering around, eating, just doing normal stuff. I’m only human after all.

Me though? Nope. Can’t do it. Twenty years and twenty pounds ago, maybe. I know that’s just my own insecurity as I know no one would give a shit if I sat here typing this blog post without a stitch of clothing on. People would probably only acknowledge my tattoos and not my 46 year old tummy and a bum that could really be a lot perkier than it is. It’s my hang up, not theirs.

On the other hand, I’m intrigued. Part of this trip for me is about saying “yes” more and learning how to unlearn many of my bad habits and shed my personal hangups. After all, when again will I be on a nude beach in Mexico, surrounded by friendly, naked French people.

So maybe, just maybe, I’ll try it. I’ll try to shed hangups along with some clothes. Maybe tomorrow, but only topless. I might be 46 but I still have a pretty nice rack.

When I was a kid my mom tended a small thatch of milkweed plants behind our garden. I remember playing with the plants, letting the sticky, white sap ooze over my hands like glue only vaguely aware that these plants were here for a purpose much bigger than my entertainment.

They were for the monarchs.

Oklahoma lies in the direct path of the monarch migration from their winter home in the states of Michoacan and Mexico in south central Mexico. They migrate each spring along specific corridors north through the United States to lay their eggs. While the adult monarch eats nectar from a variety of flowering plants the eggs can only be laid on milkweed and the larvae feed only on this plant until they emerge from their chrysalis as a full fledged orange beauty. Startlingly, up to four generations will live and die during the yearly migration.

I remember seeing the occasional orange flutter behind the garden during Oklahoma springs but it wasn’t until much later that I learned much more about the monarchs, their behavior, and the possibility that they’ll die off due to pesticide use and habitat loss.

“Flight Behavior” by Barbara Kingsolver tells the tale of a woman living in rural Tennessee who discovers a colony of monarchs in the high forest of her property. It’s winter and they shouldn’t be there; they should be in Mexico. Barbara Kingsolver weaves together the science of the butterfly migration with the angst of the main character who desperately wants to take action but feels as if she can’t, which reflects almost every aspect of her own life.

I loved the book for the book itself but it also piqued my interest about the monarchs. How do they know where to go? How do they find this certain high section of forest in rural Mexico? What would it look like to see an entire tree covered in clumps of butterflies thousands deep?

I decided to find out.

Our route through Mexico started out as a ragged, back and forth meandering but then we kind of got our groove and decided what we wanted to see and how to manage the drive to accommodate those things. One of my choices was the butterflies.

So as we headed deep into the state of Michoacan and pine forests of the Mexican Volcanic Belt I had no idea what to expect. But as I watched the altimeter on my phone climb higher and higher until we hit 9,400 feet at the visitor’s center I knew one thing for certain; we were in for a cold night.

Early the next morning we were first in line at the hitching post where the horses were waiting, wooly winter coats already in place, vapor coming out of their nostrils. Hiking to the top is also an option but when given the chance to ride, I ride. The scenery was exquisite.

So as we set out up the steep trail it only took the horses about 15 minutes to get to the place where we had to finish on foot. That hike topped us off at 11,000 feet.

It’s hard to describe what it looks like. The sun was just starting to hit the tops of the trees which were covered in brown clumps that could have been leaves. Then as the sun moved higher the clumps began to move, shiver, flashes of orange appeared and then once they were warm enough they flew. The sky filled with monarchs as the heat from the sun continued to increase.

This is literally one of those experiences you have to see to believe. No camera can do this phenomenon justice. And the sound? You simply can’t believe the sound. We were the only ones up there for about 20 minutes and as the butterflies warm up and begin to move their wings you can hear it. It sounds like the delicate rustle of a skirt made from fine fabric whose wearer is trying to move quietly. It’s all around you; you can’t not hear it.

So I just sat there on a cold rock, moving every so often to take a photo. Will and I were quiet, exchanging glances every so often that said, “Can you believe this?”

When the next groups of tourists began to arrive we decided to go, making the hike back to our horses and then rode the rest of the way down the mountain. And just like that it was over. We broke camp and hit the road.

My favorite part of this is the fact that we didn’t plan it. The butterflies are only in this part of Mexico from November until March. Had we been further south on our journey we would have missed it.

Some scientists think that the butterflies navigate by a chemical GPS system based on the position of the sun. Migration is embedded in their DNA.

I think I have some of that DNA too.

One of the things about this trip that has bothered me is that we just don’t seem to do anything. If you saw Will’s latest post and the map that accompanied it it looks like we’re just driving back and forth aimlessly and in a way we were. It was hard but Will had work obligations that kept up restricted to the north central areas and western coast.

While we definitely saw and experienced some incredible things I started to feel lost. I felt like we were just driving this road for the sake of driving it and neglecting the fact that there are so many stupefying things about Mexico that we were missing.

Of course, we can’t see it all, but we did resolve to do a little more planning and a lot more sight seeing. And it turns out that Guanajuato is the perfect place to do that. So what did we choose as our first major sightseeing tour?

The Guanajuato mummies of course.

I love creepy shit. I love macabre history and if there’s evidence of it I’ll pay the entrance fee, no questions asked. But the Guanajuato mummies takes macabre to a whole new level. I’ve seen mummies before; Peru and Egypt are rife with mummies. Even that little mummy found in Peru that many thought to be of alien origin piqued my interest (yeah, I like aliens and haunted stuff too) even though I’ve seen little in the way of credible information to indicate that it was an alien.

But back to the Guanajuato mummies. This case is so fascinating and so weird that I’m surprised everyone in the world doesn’t know about. Hell, even Werner Herzog used some footage from the museum for his film “Nosferatu the Vampyre” and that was back in the1970’s. But the interesting fact about these mummies is that they weren’t intended to be mummies at all. They just died.

Of cholera.

By most accounts the cholera outbreak occurred in Guanajuato in the early 1830’s. The dead were buried and no one thought much of it until 1870 when the municipality decided to enact a burial tax, meaning that if you wanted the body of your loved one to stay in the ground you had to pay for it. Obviously, not everyone had that kind of money laying around so the disinterment began.

The workers who were tasked with this grisly job began to notice that many of the bodies were in surprisingly good condition and these specimens were placed in a nearby warehouse. Some scientists believe that the altitude and relatively dry climate of Guanajuato caused the mummification and some say that the bodies were at least partially embalmed. Regardless, many of the Guanajuato mummies still have hair on their heads, I spied a beard, their clothing is relatively intact, and the honor of the world’s smallest mummy goes to the mummified fetus of a pregnant woman who fell to the cholera outbreak.

By the 1900’s the workers began charging people a few pesos to see the bodies and then the museum was officially opened in 1969. If you’re ever in Guanajuato and don’t mind strolling through a building full of dead people, I highly recommend it.

These are some of my favorite photos from our visit.

Scroll down if you dare.

You’ve made it this far! Congratulations! Now head to Mexico and see the Guanajuato mummies for yourself.